Adventures in Python Static Analysis

I had an opportunity, in mid-2017, to work on tooling to weed out dead code from one of the codebases I work on at Jumo¹. We use an in-house framework for building USSD² applications, the main mode of interaction users have with our lending platform.

There isn’t much of a FOSS USSD ecosystem, so the framework had to solve a lot of basic problems in novel ways. Some of the most interesting aspects of it have to do with session management - USSD being a stateless protocol without any widely adopted session management standards, and a metaclass³ based routing model. We experienced some growing pains around this, as both the team, and the product pipeline expanded. Debugging, for instance, often proved difficult as we had entire user journeys left behind by feature development. The routing registry uses string based keys, rather than actual references, making it difficult for automated tools to tell apart dead from “living” code. You could rely on grep to an extent to naively check which handler classes - somewhat analogous to a view/controller hybrid in a typical MVC model - are linked to by others, but that didn’t reveal end-to-end flow information.

This set of problems proved to be a headache for feature development, as modules grew to unmanageable sizes, slowing down delivery.

Having had some prior experience building parsers in Python, this seemed as good a chance as any to exercise what little knowledge I had lingering from Compilers 101.

Tool survey

During an internship with Wezatele, one of the predecessor companies to Jumo, I had a chance to work on a pseudo-natural language driven SMS-based ordering system. I don’t know if it ever went into production, but it was some of the most technically fulfilling work I had done (and have done) up until now. The “pseudo” is important. It was actually just a constrained DSL allowing customers to place orders without access to an Internet connected device. This was a time before wide smartphone penetration in Kenya, so it was essential to target low tech devices.⁴ I still remember my prized Nokia N97, then, to my young mind, the pinnacle of technical refinement, before the infamous burning platform memo that presaged the downfall of Nokia. But I digress…

For that particular problem, the CTO suggested PyParsing⁵, a library for - you guessed it - building parsers in Python. With that background, my first thought was to build a parser that understood the intricacies of the USSD framework routing protocol. I quickly realised that it would have been a fool’s errand to attempt to write a full blown Python parser, as several already existed, but whatever solution there was had to have high-level semantics for me to work with it comfortably. That’s when I stumbled upon the Python ast⁶ module. It ships with the standard library, and is essentially a wrapper around the lower level _ast module. (Note the underscore).

Static analysis enables you to inspect code without actually running it, which helps keep build times short.

The approach I took boiled down, in essence, to

- Reading source files into strings.

- Parsing the source into a high level Abstract Syntax Tree representation using ast.parse.

- Filtering to only subclasses of the base handler class, which were the most affected by the dead code scourge.

- Flattening the AST nodes nested within each class to pull out the routing information. There were multiple different ways, each suited to different contexts, for doing this. These were, thankfully, widely understood within the team. As a precursor to this line of work, I worked on a document detailing the internals of the framework. One did not exist yet, as development had been driven organically by product needs up until that point.

- The code would then construct all possible routes from each handler, and use that to build a tree detailing, from start to finish, all possible user journeys supported by the handlers in question.

- Given these possible paths, the correct one would be determined by filtering out those that didn’t start from the known correct starting point. These would then be returned as a list of “dead handlers”.

- I then wrote a Django⁷ management command that would accept as parameters, the file path to a module containing handlers, and the starting point.

This led to a great reduction in dead code, though some of the checks resulted in false positives. Our CI⁸ tool would flag any dead code with a broken build, allowing reviewers to add false positives to a whitelist to reduce noise.

A quick primer

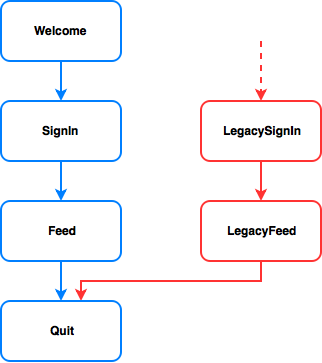

Given the following code, loosely mimicking the USSD framework handler model, your task is to determine which handlers are no longer part of the user journey.

handlers.py

class Welcome(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if request.user.is_logged_in:

return request.redirect('Feed')

else:

return request.redirect('SignIn')

class SignIn(Handler):

next_handler = 'Feed'

class Feed(Handler):

next_handler = 'Quit'

def handle(self, request):

return self.display("What's happening")

class LegacySignIn(Handler):

previous_handler = 'LegacyWelcome'

def handle(self, request):

if request.user.has_active_subscription:

return request.redirect('LegacyFeed')

else:

return self.display('Please supply your credentials')

class LegacyFeed(Handler):

next_handler = 'Quit'

def handle(self, request):

return self.display("What happened back then")

class SomeUtilityClass:

def do_useful_stuff(self):

return self.done()

class Quit(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

return self.display('Adios!')

def some_utility_function(params):

return do_stuff_with_the_params(params)

detectors.py

from ast import parse

from _ast import ClassDef, FunctionDef, Assign, If, Expr, Call, Return

from operator import concat

def is_class(node):

return isinstance(node, ClassDef)

def is_handler(node):

type_ids = map(lambda base: base.id, node.bases)

return reduce(

lambda type_id, id_is_Handler: type_id is 'Handler' or id_is_Handler,

type_ids,

None

)

def get_ast(module_path):

with open(module_path) as module_file:

source = module_file.read()

tree = parse(source).body

return tree

def get_handler_nodes(tree):

classes = filter(lambda node: isinstance(node, ClassDef), tree)

handlers = filter(is_handler, classes)

return handlers

def deconstruct_body(node):

accumulator = []

if hasattr(node, 'body'):

accumulator.extend(map(deconstruct_body, node.body))

if hasattr(node, 'orelse'):

accumulator.extend(map(deconstruct_body, node.orelse))

else:

accumulator.append(node)

return accumulator

def flatten_nodes(deconstructed_handler_body):

accumulator = []

for item in deconstructed_handler_body:

if isinstance(item, list):

accumulator.extend(flatten_nodes(item))

else:

accumulator.append(item)

return accumulator

def is_assignment_exit_path(node):

return isinstance(node, Assign) and node.targets[0].id in ['next_handler', 'previous_handler']

def extract_exit_path(node):

if isinstance(node, Assign) and node.targets[0].id in ['next_handler', 'previous_handler']:

return node.value.s

elif isinstance(node, Return) and isinstance(node.value, Call) and node.value.func.attr == 'redirect' and node.value.func.value.id == 'request':

return node.value.args[0].s

def get_handler_exit_paths(handler_class_ast):

deconstructed_body = deconstruct_body(handler_class_ast)

flat_node_list = flatten_nodes(deconstructed_body)

return (

handler_class_ast.name,

filter(

lambda exit_path: exit_path is not None,

reduce(

lambda exit_path_list, node: [extract_exit_path(node)] + exit_path_list,

flat_node_list,

[]

)

)

)

def is_handler_in_journey(test_handler, initial_handler, exit_path_registry):

if test_handler == initial_handler:

return True

exit_paths = exit_path_registry[initial_handler]

if len(exit_paths) == 0: return False

for handler in exit_paths:

if test_handler == handler:

return True

else:

return is_handler_in_journey(test_handler, handler, exit_path_registry)

test.py

def test_handler_is_in_journey(handler_to_test, initial_handler, module_path):

module_ast = get_ast(module_path)

handler_nodes = get_handler_nodes(module_ast)

exit_path_registry = dict(

map(

get_handler_exit_paths,

handler_nodes

)

)

assert is_handler_in_journey(handler_to_test, initial_handler, exit_path_registry)

The code below passes silently

test_handler_is_in_journey('SignIn', 'Welcome', 'handlers.py')

The code below throws an AssertionError

test_handler_is_in_journey('LegacySignIn', 'Welcome', 'handlers.py')

Final Words

While this particular illustration is quite specific to the Jumo context, these same tools and approaches can be used to reduce manual effort in your development workflow. An example would be detecting unused views in a web application that uses string-based routing.

References

² Unstructured Supplementary Service Data: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unstructured_Supplementary_Service_Data

³ http://python-3-patterns-idioms-test.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Metaprogramming.html

⁴ As a side note, it’s only now struck me that most of my career has been around targeting low tech delivery media.

⁵ PyParsing: http://pyparsing.wikispaces.com/

⁶ https://docs.python.org/2/library/ast.html

⁷ Django: https://www.djangoproject.com/

⁸ Continuous Integration: https://www.thoughtworks.com/continuous-integration